Review of Natalie Bauer Lechners Recollections of Mahler

| Symphony No. 2 | |

|---|---|

| Resurrection Symphony | |

| by Gustav Mahler | |

Mahler in 1892 | |

| Primal | C minor – East-apartment major |

| Text |

|

| Language | German |

| Composed | 1888–1894 |

| Published | 1897 (1897) (Friedrich Hofmeister Musikverlag) |

| Recorded | 1924 (1924) Oskar Fried, Berlin State Opera Orchestra |

| Movements | 5 |

| Scoring |

|

| Premiere | |

| Date | 13 December 1895 (1895-12-13) |

| Location | Berlin |

| Conductor | Gustav Mahler |

| Performers | Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra |

The Symphony No. two in C small by Gustav Mahler, known every bit the Resurrection Symphony , was written between 1888 and 1894, and beginning performed in 1895. This symphony was 1 of Mahler'southward well-nigh pop and successful works during his lifetime. Information technology was his first major work that established his lifelong view of the dazzler of afterlife and resurrection. In this large piece of work, the composer further developed the creativity of "sound of the distance" and creating a "world of its ain", aspects already seen in his First Symphony. The work has a duration of 80 to 90 minutes, and is conventionally labelled as existence in the key of C pocket-size; the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians labels the piece of work'south tonality as C small–East ♭ major.[1] It was voted the fifth-greatest symphony of all time in a survey of conductors carried out by the BBC Music Magazine.[ii]

Origin [edit]

Mahler completed what would get the first movement of the symphony in 1888 as a unmarried-move symphonic poem called Totenfeier (Funeral Rites). Some sketches for the 2nd motility too engagement from that year. Mahler wavered v years on whether to make Totenfeier the opening movement of a symphony, although his manuscript does characterization information technology as a symphony. In 1893, he composed the 2nd and third movements.[iii] The finale was the problem. While thoroughly aware he was inviting comparison with Beethoven'southward Symphony No. ix—both symphonies utilize a chorus every bit the centerpiece of a final movement which begins with references to and is much longer than those preceding it—Mahler knew he wanted a vocal final movement. Finding the right text for this movement proved long and perplexing.[4]

When Mahler took up his date at the Hamburg Opera in 1891, he constitute the other important usher there to be Hans von Bülow, who was in charge of the city'southward symphony concerts. Bülow, not known for his kindness, was impressed by Mahler. His back up was not diminished by his failure to like or understand Totenfeier when Mahler played it for him on the piano. Bülow told Mahler that Totenfeier made Tristan und Isolde audio to him like a Haydn symphony. As Bülow's health worsened, Mahler substituted for him. Bülow'southward death in 1894 greatly afflicted Mahler. At the funeral, Mahler heard a setting of Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock's poem "Die Auferstehung" (The Resurrection), where the dictum calls out "Rise over again, yes, you shall ascension again / My dust".

"It struck me like lightning, this thing," he wrote to conductor Anton Seidl, "and everything was revealed to me clear and plain." Mahler used the offset 2 verses of Klopstock's hymn, then added verses of his own that dealt more explicitly with redemption and resurrection.[5] He finished the finale and revised the orchestration of the commencement motility in 1894, so inserted the song "Urlicht" (Key Light) as the penultimate motion. This vocal was probably written in 1892 or 1893.[three]

Shorthand manuscript of the symphony

Mahler initially devised a narrative programme (actually several variant versions) for the work, which he shared with a number of friends (including Natalie Bauer-Lechner and Max Marschalk). He fifty-fifty had one of these versions printed in the program book at the premiere in Dresden on 20 December 1901. In this programme, the first movement represents a funeral and asks questions such equally "Is there life later death?"; the second movement is a remembrance of happy times in the life of the deceased; the 3rd movement represents a view of life every bit meaningless activity; the fourth motility is a wish for release from life without meaning; and the fifth movement – afterward a return of the doubts of the third movement and the questions of the first – ends with a fervent hope for everlasting, transcendent renewal, a theme that Mahler would ultimately transfigure into the music of Das Lied von der Erde.[half dozen] As by and large happened, Mahler later withdrew all versions of the programme from circulation.

Publication [edit]

The work was kickoff published in 1897 by Friedrich Hofmeister. The rights were transferred to Josef Weinberger shortly thereafter, and finally to Universal Edition, which released a second edition in 1910. A tertiary edition was published in 1952, and a 4th, critical edition in 1970, both by Universal Edition. As function of the new complete critical edition of Mahler'due south symphonies being undertaken by the Gustav Mahler Order, a new critical edition of the Second Symphony was produced as a articulation venture between Universal Edition and the Kaplan Foundation. Its world premiere performance was given on 18 October 2005 at the Royal Albert Hall in London with Gilbert Kaplan conducting the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.[vii]

Reproductions of earlier editions have been released by Dover and by Boosey & Hawkes. The Kaplan Foundation published an extensive facsimile edition with additional materials in 1986.[eight] 1989 saw the publication of an arrangement by Bruno Walter for piano four hands.[ix]

Instrumentation [edit]

The symphony is scored for large orchestra, consisting of the following:

- Woodwinds

- four flutes (all doubling piccolos)

- 4 oboes (tertiary doubling cor anglais, 4th used only in movement 5, doubling cor anglais)

- 3 B ♭ , A, C clarinets (tertiary doubling bass clarinet)

- ii E ♭ clarinets (2nd doubling 4th clarinet, both doubling fortissimo[ clarification needed ] where possible)

- 4 bassoons (third doubling contrabassoon, quaternary used simply in motility 5 and doubling contrabassoon)

- Brass

- 10 horns (7th–10th used only in motion five, both offstage and onstage)

- 10 trumpets (fifth and 6th used but in movement v, onstage. 7th–10th used only in movement 5, offstage)

- 4 trombones

- tuba

- Percussion

- 2 sets of timpani (a third histrion is required but only in motion five, offstage)

- two bass drums (second with a cymbal attached, used only in movement 5, offstage)

- several snare drums (used only in motility 5)

- Pair of cymbals

- 2 triangles (2d used just in movement 5, offstage)

- 2 tam-tams (high and low)

- rute (used only in move three)

- 3 deep, untuned bells (used but in movement 5)

- glockenspiel

Form [edit]

The work in its finished grade has five movements:

I. Allegro maestoso [edit]

The start motion is marked Mit durchaus ernstem und feierlichem Ausdruck (With complete gravity and solemnity of expression). It is written in C minor, but passes through a number of different moods and resembles a funeral march.

![\relative c' { \clef treble \numericTimeSignature \time 4/4 \key c \minor c1-^\p | d2^^ f4.^^ aes8-. | c2^^ g4.^^ g8-. | c2^^ \times 2/3 { r8 r8 c-. } \times 2/3 { d-. c-. b-. } | c8-.[ r16 g-.] c,8-. }](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/r/8/r8trn3akqhqmzo8yfszoin54xa9pmm0/r8trn3ak.png)

The movement'south formal structure is modified sonata form. The exposition is repeated in a varied grade (from rehearsal number 4 through 15, as Ludwig van Beethoven ofttimes did in his late cord quartets). The development presents several ideas that will exist used later in the symphony, including a theme based on the Dies irae plainchant.

Mahler uses a somewhat modified tonal framework for the motion. The secondary theme, commencement presented in East major (enharmonic of F ♭ major, Neapolitan of East ♭ ),[ten]

begins its second statement in C major, a cardinal in which it is not expected until the recapitulation. The statement in the recapitulation, coincidentally, is in the original E major (F ♭ major). The eventual goal of the symphony, Eastward-flat major, is briefly hinted at afterwards rehearsal 17, with a theme in the trumpets that returns in the finale.

![\relative c'' { \clef treble \numericTimeSignature \fourth dimension 4/4 \central ees \minor <bes g ees>two^^\p <c aes ees>^^ | <ees bes ees,>^^ r4 f, | k^^ bes^^\< ees^^ d8[\!-. r16 c-.] | bes1\f }](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/eastward/vi/e6idcq7prw6hqpkg6tfkzfehmieitvh/e6idcq7p.png)

Post-obit this movement, Mahler calls in the score for a gap of v minutes before the second movement. This suspension is rarely observed today. Frequently conductors will encounter Mahler half way, pausing for a few minutes while the audition takes a sabbatical and settles down and the orchestra retunes in preparation for the residuum of the piece. Julius Buths received this instruction from Mahler personally, prior to a 1903 performance in Düsseldorf;[11] however, he chose instead to identify the long pause between the fourth and 5th movements, for which Mahler congratulated him on his insight, sensitivity, and daring to go against his stated wishes.[12]

A practical mode of following Mahler's original indication is to have the two soloists and the chorus enter the stage simply afterward the commencement movement. This creates a natural separation between the start motility and the remainder of the symphony and also saves the singers more than twenty minutes of sitting on phase. One can go an idea of Mahler'southward intention through a comparison with his Symphony No. 3, where – due to the length of the piece – a real break later on the start movement (equally between two acts of an opera) is highly recommended, and indeed indicated by Mahler. Every bit in the case of Symphony No. 2, this is not always observed nowadays.

II. Andante moderato [edit]

The 2d movement is marked Sehr gemächlich. Nie eilen. (Very leisurely. Never rush.) It is a frail Ländler in A ♭ major.

with two contrasting sections of slightly darker music.

![\relative c'' { \clef treble \time 3/8 \key gis \minor \tempo 8 = 92 \partial 8*1 \times 2/3 { dis'16-.\ppp cisis-. dis-. } | \times 2/3 { e-.[ dis-. cis!-.] } \times 2/3 { b-.[ ais-. gis-.] } \times 2/3 { fisis-.[ gis-. ais-.] } | \times 2/3 { gis^^([ dis-.) dis-.] } \times 2/3 { dis-.[ dis-. dis-.] } \times 2/3 {dis-.[ dis-. dis-.] } }](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/4/4/44vd75k86m3wyfmfps4qmvt24ldii35/44vd75k8.png)

This slow movement itself is contrasting to the two adjacent movements. Structurally, it is one of the simplest movements in Mahler's whole output. It is the remembrance of the joyful times in the life of the deceased.

III. In ruhig fließender Bewegung (With quietly flowing movement) [edit]

The third motion is a scherzo in C minor. It opens with ii strong, short timpani strokes.

It is followed by two softer strokes, and so followed past even softer strokes that provide the tempo to this movement, which includes references to Jewish folk music.

Mahler called the climax of the movement, which occurs nearly the end, sometimes a "cry of despair", and sometimes a "expiry shriek".

The movement is based on Mahler's setting of "Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt" from Des Knaben Wunderhorn, which Mahler composed almost concurrently; in correspondence, Mahler expressed amusement that his sinuous musical setting could imply St. Anthony of Padua was himself drunk as he preached to the fish.[13] In 1967–68, the movement was used by Luciano Berio for the 3rd movement of his Sinfonia, where it is used as the framework for amalgam a musical collage of works from throughout the Western classical tradition.

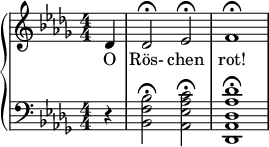

IV. "Urlicht" [edit]

The fourth move, "Urlicht" (Primal Light) is marked Sehr feierlich, aber schlicht (Very solemn, but simple). It is a Wunderhorn song, sung by an alto, which serves as an introduction to the Finale. The vocal, prepare in the remote key of D ♭ major, illustrates the longing for relief from worldly woes, leading without a intermission to the response in the Finale.

V. Im Tempo des Scherzos (In the tempo of the scherzo) [edit]

The finale is the longest movement, typically lasting over one-half an hour. It is divided into ii large parts, the 2d of which begins with the entry of the chorus and whose course is governed by the text of this movement. The first part is instrumental, and very episodic, containing a wide variety of moods, tempi and keys, with much of the material based on what has been heard in the previous movements, although information technology also loosely follows sonata principles. New themes introduced are used repeatedly and altered.

The movement opens with a long introduction, kickoff with the "cry of despair" that was the climax of the third movement, followed by the placidity presentation of a theme which reappears as structural music in the choral section,

and by a call in the offstage horns.

The showtime theme grouping reiterates the Dies irae theme from the showtime movement, so introduces the "resurrection" theme to which the chorus will sing their first words, and finally a fanfare.

The second theme is a long orchestral recitative, which provides the music for the alto solo in the choral section.

The exposition concludes with a restatement of the first theme group. This long opening department serves to innovate a number of themes, which will become important in the choral part of the finale.

The development section is what Mahler calls the "march of the expressionless". It begins with ii long drum rolls, which include the use of the gongs. In add-on to developing the Dies irae and resurrection themes and motives from the opening cry of despair, this department too states, episodically, a number of other themes, based on earlier cloth. The recapitulation overlaps with the march, and only brief statements of the beginning theme group are restated. The orchestral recitative is fully recapitulated, and is accompanied this time by offstage interruptions from a band of contumely and percussion (which some had explained as the apocalypse's seven trumpets). This builds to a climax, which leads into a restatement of the opening introductory section. The horn call is expanded into Mahler's "Great Summons", a transition into the choral section.

Tonally, this showtime big role, the instrumental half of the movement, is organized in F minor. Subsequently the introduction, which recalls two keys from earlier movements, the first theme group is presented wholly in F minor, and the 2nd theme group in the subdominant, B ♭ pocket-size. The restatement of the offset theme grouping occurs in the dominant, C major. The development explores a number of keys, including the mediant, A ♭ major, and the parallel major, F major. Dissimilar the get-go movement, the second theme is recapitulated as expected in the tonic key. The restatement of the introduction is thematically and tonally a transition to the second large function, moving from C ♯ small to the parallel D ♭ major — the ascendant of F ♯ pocket-size — in which the Great Summons is stated. The Epiphany comes in, played by the flute, in a high register, and featuring trumpets, that play offstage. The choral department begins in G ♭ major.

The chorus comes in quietly a piffling past the halfway betoken of the movement.

The choral section is organized primarily past the text, using musical material from earlier in the movement. (The B ♭ below the bass clef occurs 4 times in the choral bass part: iii at the chorus' hushed entrance and again on the words "Hör' auf zu beben". It is the everyman vocal notation in standard classical repertoire. Mahler instructs basses incapable of singing the note remain silent rather than sing the note an octave college.) Each of the first two verses is followed by an instrumental interlude; the alto and soprano solos, "O Glaube",

based on the recitative melody, precede the fourth verse, sung past the chorus; and the 5th verse is a duet for the two soloists. The opening two verses are presented in G ♭ major, the solos and the fourth poesy in B ♭ pocket-sized (the key in which the recitative was originally stated), and the duet in A ♭ major. The goal of the symphony, E ♭ major, the relative major of the opening C minor, is achieved when the chorus picks up the words from the duet, "Mit Flügeln",

although later on viii measures the music gravitates to Thou major (only never cadences on it).

East ♭ suddenly reenters with the text "Sterben werd' ich um zu leben," and a proper cadency finally occurs on the downbeat of the final verse, with the entrance of the heretofore silent organ (marked volles Werk, total organ) and with the choir instructed to sing mit höchster Kraft (with highest ability). The instrumental coda is in this ultimate cardinal equally well, and is accompanied by the tolling of deep bells. Mahler went so far as to buy actual church bells for performances, finding all other ways of achieving this sound unsatisfactory. Mahler wrote of this motility: "The increasing tension, working upwards to the concluding climax, is so tremendous that I don't know myself, at present that it is over, how I ever came to write information technology."[14]

Text [edit]

Note: This text has been translated from the original High german text from Des Knaben Wunderhorn to English on a very literal and line-for-line basis, without regard for the preservation of meter or rhyming patterns.

Fourth movement [edit]

Urlicht

O Röschen rot!

Der Mensch liegt in größter Not!

Der Mensch liegt in größter Pein!

Je lieber möcht' ich im Himmel sein.

Da kam ich auf einen breiten Weg:

Da kam ein Engelein und wollt' mich abweisen.

Ach nein! Ich ließ mich nicht abweisen!

Ich bin von Gott und volition wieder zu Gott!

Der liebe Gott wird mir ein Lichtchen geben,

wird leuchten mir bis in das ewig selig Leben!

—Des Knaben Wunderhorn

Earliest Light

O little red rose!

Human lies in greatest need!

Man lies in greatest pain!

How I would rather be in sky.

There came I upon a broad path

when came a niggling affections and wanted to plow me abroad.

Ah no! I would not let myself be turned abroad!

I am from God and shall return to God!

The loving God will grant me a niggling light,

Which volition calorie-free me into that eternal blissful life!

Fifth movement [edit]

Notation: The first viii lines were taken from the verse form "Dice Auferstehung" by Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock.[fifteen] Mahler omitted the final four lines of this poem and wrote the remainder himself (beginning at "O glaube").

Aufersteh'northward, ja aufersteh'northward wirst du,

mein Staub, nach kurzer Ruh'!

Unsterblich Leben! Unsterblich Leben

volition der dich rief dir geben!

Wieder aufzublüh'north wirst du gesät!

Der Herr der Ernte geht

und sammelt Garben

uns ein, dice starben!

—Friedrich Klopstock

O glaube, mein Herz, o glaube:

es geht dir nichts verloren!

Dein ist, ja dein, was du gesehnt,

dein, was du geliebt,

was du gestritten!

O glaube,

du warst nicht umsonst geboren!

Hast nicht umsonst gelebt,

gelitten!

Was entstanden ist,

das muss vergehen!

Was vergangen, aufersteh'northward!

Hör' auf zu beben!

Bereite dich zu leben!

O Schmerz! Du Alldurchdringer!

Dir bin ich entrungen!

O Tod! Du Allbezwinger!

Nun bist du bezwungen!

Mit Flügeln, die ich mir errungen,

in heißem Liebesstreben,

werd' ich entschweben

zum Licht, zu dem kein Aug' gedrungen!

Sterben werd' ich, um zu leben!

Aufersteh'northward, ja aufersteh'n wirst du

mein Herz, in einem Nu!

Was du geschlagen

zu Gott wird es dich tragen!

—Gustav Mahler

Ascension again, aye, rise once more,

Will you lot, my grit, after a brief remainder!

Immortal life! Immortal life

Will he who called you, give you.

You lot are sown to bloom once more!

The lord of the harvest goes

And gathers sheaves,

Us, who have died.

O believe, my heart, O believe:

Zippo is lost to you!

Yours, aye yours, is what you desired

Yours, what you have loved

What you have fought for!

O believe,

You were non born for nothing!

Take not lived for nothing,

Nor suffered!

What was created

Must perish;

What perished, rise again!

Terminate from trembling!

Fix yourself to live!

O Pain, you piercer of all things,

From you, I have been wrested!

O Death, you conqueror of all things,

Now, are you conquered!

With wings which I have won for myself,

In love'south fierce striving,

I shall soar upwards

To the light which no eye has penetrated!

I shall dice in order to live.

Ascent again, yeah, rise once again,

Will you, my heart, in an instant!

That for which yous suffered,

To God shall information technology carry you lot!

Premieres [edit]

- World premiere (get-go three movements only): March 4, 1895, Berlin, with the composer conducting the Berlin Combo.[16]

- World premiere (consummate): December 13, 1895, Berlin, conducted by the composer.[17]

- Belgian premiere: March six, 1898, Liège, 'Nouveaux Concerts', conducted by Sylvain Dupuis. This was the starting time performance outside Germany.[18]

Score [edit]

The original manuscript score was given by Mahler'south widow to conductor Willem Mengelberg at a 1920 Mahler festival given past Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw Orchestra. It was bought from the Mengelberg Foundation in 1984 past entrepreneur Gilbert Kaplan, who specialised in conducting the symphony as an amateur.[8]

On 29 Nov 2016 the score was sold at Sotheby's of London for £4.v million, the highest price for a musical manuscript ever sold at auction. In that location were four telephone bidders for the manuscript, with the winning applicant choosing to remain bearding.[19]

References [edit]

- ^ "Gustav Mahler", in New Grove, Macmillan, 1980

- ^ Mark Brown Arts correspondent (four Baronial 2016). "Beethoven's Eroica voted greatest symphony of all time". The Guardian . Retrieved 2020-05-01 .

- ^ a b Steinberg 1995, p. 285.

- ^ Steinberg 1995, pp. 290–291.

- ^ Steinberg 1995, p. 291.

- ^ "Symphony No. 2 in C minor (Resurrection)". Kennedy Heart for the Performing Arts. Archived from the original on Oct xix, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-24 .

- ^ "Mahler Premiere". classicalsource.com. Retrieved 29 Nov 2016.

- ^ a b "Gilbert Kaplan (1941–2016)". gustav-mahler.eu. Retrieved xx December 2018.

- ^ Symphony No. ii – Arrangements and transcriptions: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- ^ Schram, Albert-George. Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 2 (C minor): A Historical Background and Analysis. Thesis (D.Mus. Arts) University of Washington, 1985.

- ^ "San Francisco Symphony – Program Notes & Articles". sfsymphony.org. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ "Monthly Calendar – November 2016". kennedy-centre.org. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ "Des Knaben Wunderhorn". kennedy-centre.org. Retrieved 20 Dec 2018.

- ^ Natalie Bauer-Lechner, Recollections of Gustav Mahler, trans. Dika Newlin, ed. Peter Franklin (New York: Cambridge University Printing, 1980), pp. 43–44.

- ^ Klopstock'due south poem "Dice Auferstehung" is non, as is normally believed, i of his Oden, but rather from the 1758 collection Geistliche Lieder (Spiritual Songs).

- ^ "1895 Concert Berlin 04-03-1895 – Symphony No. ii – movement 1, 2 and 3". Mahler Foundation. 28 February 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "1895 Concert Berlin 13-12-1895 – Symphony No. ii (Premiere)". Mahler Foundation. 5 March 2016. Retrieved 12 Nov 2021.

- ^ Henry-Louis de La Grange, Gustav Mahler, vol. 2: Vienna: The Years of Claiming (1897–1904), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995, pp. 85–86

- ^ "Gustav Mahler £four.5m manuscript breaks record at Sotheby's". BBC News. 29 Nov 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

Sources

- Steinberg, Michael (1995). The Symphony . New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN0-nineteen-506177-2.

External links [edit]

- Symphony No. 2: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Classical Notes

- "Mahler's Second: The Story within the Symphony", WQXR Radio, 18 February 2012

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symphony_No._2_%28Mahler%29

0 Response to "Review of Natalie Bauer Lechners Recollections of Mahler"

Post a Comment